The West: a Myth hard to die

What the term is intended to signify is quite obvious: The West is “our world”; the world of Human rights, of individual liberties where there are no government shackles; the world of wellness, of cinema and the arts, of classical music and rock & roll, of technological development and free elections. In other words, the West is the liberal-democratic world where progress occurs naturally in all fields of human endeavor. Consequently, while the West is that geographical space that corresponds to Euro-America, it is also and above all a cultural, legal and social space. This space traditionally includes regions such as Australia and Canada, which are, of course, colonies of Europe, the West’s original matrix. Now, if we were to stick to this bare-bones definition – that the West is the geographical and cultural context of liberal-democracy, of modern Euro-America – there would really be nothing to object at all. We could even agree with those who sing “The praise of the West” by stating that, notwithstanding all its shortcomings, the West continues to be the “the best possible world” or at least the most viable. Or, we could even be on the side of those who point to the West’s countless wars (civil wars, wars of conquests and extermination, atomic war) and that the pain and destruction cannot be ascribed solely on the wars it gas unleashed. Consider only that this land of liberty is also the land of consumption where 20% of “Westerners” consume around 80% of the word’s available resources.

Alternatively, we could remind liberal and democratic Euro-America that the consolidation of this ideology and system of life have occurred in a period of just under a century, without considering that in a number of European countries a fully-developed liberal-democratic system continues to be elusive. And the same could be said about the press and the media. Institutional turnover, too, doesn’t always take place. In this light, we could also recall that racism, apartheid and other discriminatory systems were not the exclusive heritage of European regimes like Fascism and Nazism, but also of very democratic ones. America is a country that founded part of its history and economy on racism and all its related repercussions in terms of injustice, of exploitation and of the denial of the most elementary rights of freedom and equality, not to mention of solidarity, which is the foundation of democracy both ancient and modern.

This bright picture of a West that is wealthy and industrious, free, supportive and welcoming, the place where justice reigns, is flawed and smeared. In some cases these smears are blood red. Therefore, the West doesn’t correspond to the Land of Toys, where Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio is taken to. Nor is it the Island of the Blessed that Plato among others mentions. Thus, when I say that the West is a myth that is hard to die I’m also bringing to the fore a critique on the idealization of the so-called “Western model”. From another point of view, the West and its civilization could be defined as a “Myth”, inasmuch as it is an ideological construction, a political artefact.

It is this latter perspective that my book The Myth of Western Civilization explores.

Nevertheless, we must take a step back. Many among those who claim the paramountcy of the West and its system of life – because this is what it is all about – are also at the same time convinced that the West has a long history and that western civilization doesn’t only concern modernity – of victorious modernity. In academic circles as well as in the world of cultural journalism there is the opinion that the West, its culture and values, have a history going well past modernity all the way to antiquity. In US universities courses were available focusing on Western history. I imagine that these courses were highly diversified because “westernists” have each their own version of the West and its many and sundry roots. The Athens of Pericles or the Jerusalem of the Maccabees? The Paris of Robespierre or the Rome of the secular popes? The cult of the emperor or that of the Virgin Mary? Westernists have each their own West, with its toots and sanctuaries. When westernists speak of the West they are actually speaking about their very own specific West, each of whom claims it is the one and only West. But what prevails in most cultivated circles is the notion of the mixed bag West – of the Frankenstein West, or better still, of the Harlequin West. In goes just about everything: Hellenic civilization with Christianity, Judaism and Catholicism, revealed truth and rationalism, democracy and tradition. And it matters not that the one has prevailed over the other, that the beliefs of one have been cast into the fires lit by the other, that faith and agnosticism are as incompatible as is the will of the people with revelation. In that mixed-bag what matters is the lump sum which is the outcome of an ideological construction, i.e. Western Civilization.

Contents and Abstract

1. The West in the geographies of the ideological imagination >> 1

1.1 The globalized West >> 2

1.2 The West in European history >> 6

1.3 Multiple and incompatible Wests >> 8

1.4 Reactionary and traditional West >> 11

In search of the West >> 14

2. At the origins of the Myth: Persepolis versus Athens >> 15

2.1 Persepolis versus Athens? >> 15

2.2 From Sardis to Persepolis: a fire that raged for two centuries >> 19

2.3 The Persian model and the “clash of civilization” >> 28

2.4 Europe’s “natural enemy”: building the myth >> 35

2.5 A legend within a legend: Asian and/or Roman Troy >> 47

3. Is the West christian, classic and democratic? >> 65

3.1 Christianity and Christianities: the many religions of the West >> 65

3.2 On the alleged “classical roots” of the West >> 84

3.3 Jerusalem, Athens, Rome: The West’s false chronologies. >> 97

3.4 Theos, Demos, West: A troublesome relationship >> 132

Conclusive remarks: On the futility of a Myth >> 145

Comments to the Pictures >> 147

NAME INDEX >> 148

Abstract

The West as an ideological category and political myth

In many ways a study on a Myth, on an artificial and imaginary construction as is the “West”, would be pointless. It would be like an inquiry into something that doesn’t exist – an investigation on ghosts. But such an approach implies that it would be pointless to study a religion like Christianity or Islam by arguing that God doesn’t exist. In reality, in widely differing milieus, from journalism to politics, university research and religious communities, reference is constantly made to “Western Civilization”, to its culture, way of life and values, among which, first and foremost, there is “Freedom”. Generally speaking, the “West” is intended as encompassing Europe and the United States.

At the same time, advocators of the West will not admit that the so-called Western Civilization begins and ends with the development of modern liberal-democracies, they would rather believe that Western Civilization is but the final chapter of a story that started in Europe and continued also in the United States, thereby establishing an ideal and solid connection between these two continents and their people.

The numerous efforts at reconstructing a presumed history of the West – a West characterized by common values and principles – have turned out to be feeble, exposing all the fragility of a political category that has been filled with contents of varying nature, contradictory and, at times, even incompatible. In this reconstruction, relationships as well as historical and ideological connections have found no grounding in reality, as when it is pointed out that there exists some sort of affinity between Greekness and Christianity or compatibility between theocracy and democracy or between Catholicism and Enlightenment. In this way, the West becomes an artificial and ideological construction, a political myth created from the expectations and ideals of its creators: a sort of Frankenstein or Harlequin patched up by piecing together parts of European and US history with the glue of ideology. Consequently, there exists as many Wests as there are westernists, just as there are as many religions as there are persons who believe in them. A religion or an ideology don’t require objective facts; they don’t require substantiation or evidence – they need to be believed. They do not need investigators but believers.

The aim of “ The Myth of Western Civilization” is to show the inconsistency of the notion of West, a category that has been constructed on the presumed opposition between Greece/Europe and Persia/Asia, between Christianity and Islam, between the liberal-democratic and other world views. The book sheds light on the links, relations and similarities of worlds believed to be different and antagonistic, underlining at the same time the contribution of worlds like the Phoenician and the Islamic, considered to be at the opposite end of Europe. But the book also highlights the distance and contrast that exist in the Greek world and Christianity – hemispheres considered to be typically western but actually homogeneous only through simplification. And the book finally brings to light the non-plausibility of historico-ideological reconstructions that attempt to establish contiguity and interaction between Christianity and Judaism, the latter considered by the former as a heresy, or between the Christian and Greek worlds, when the latter had seen its culture, philosophy, religion, temples, books destroyed by triumphant Christianity. Enrico Ferri’s research shows how a political myth – the West – became a historica reality.

West Harlequin: one West, many West

In The Servant of Two Masters (Italian: ‘Il servitore di due padroni’), a well-known comedy by the 18th century Venetian playwright Carlo Goldoni, the main character, Harlequin, finds himself, due to unexpected twists and turns, serving two masters, a circumstance that forces him to play differing and often ambiguous roles. Without doubt the most famous character of the Venice Carnival, Harlequin stands out above all for his extravagant attire. The story has it that he hailed from a very poor family that could not afford a proper costume for the carnival. But his friends came to his aid offering each a piece of their clothes – tatters that Harlequin’s mother then stitched together to make a multi-coloured costume.

Harlequin’s characteristic chequered costume could be viewed as a metaphor of the West or the many representations that have been given of it. That motley dress, made of colourful patches, could be seen as the metaphor of the various reconstructions that have been made of the West’s identity, where different cultures, religions, histories, ideologies, economic systems and worldviews have been bundled together. The West has thus been variously seen as the outcome of the invention of the city-state and the individual; as arising from private law and property, from Graeco-Roman culture, humanism and the Enlightenment, from liberal democracy and capitalism. Or as an offshoot of values and principles such as liberty and equality. This multifarious mass of elements has acted as a source for the construction of artificial identities that very much resemble Harlequin’s patched outfit. This has led some to maintain that the West was represented initially by Christianity-Catholicism and subsequently by democracy (S. Huntington), while others believe it to be the synthesis ‘between Athens, Rome, Jerusalem’ (P. Nemo, Ratzinger).

Western identity, in the sense of a sequence of constants that weave a recurrent pattern over the centuries, does not exist. Just as non-existent is a West represented by cultures, events and ways of life that regularly succeed each other over time. On the contrary, a recurrent feature in European history has been the emergence of cultures and civilizations that have clashed with and prevailed over each other, with one often annihilating the other, as was the case with Christianity, which prevailed over Hellenic civilization, obliterating many aspects of it.

The West is thus an artificial construction, an ideological receptacle filled with contents of a highly diverse nature, often assembled in a chaotic manner. Like Harlequin’s costume!

West and East: when was Western Civilization born?

If we asked, “When were the West and Western civilization born?” the answer could be: “The West doesn’t exist, therefore it was never born.” As I indicate in my book, this answer is formally correct because the West is not a reality that can be determined, one that has a definite and documented origin, because it is a ‘Myth’. As I repeatedly point out in my book, for an ideology to be plausible it doesn’t need to be true, real, tested; it only needs to be believed. An ideology is like a religion: for it to exist, it must be accepted and shared.

The logic behind faith is unlike that on which reason is grounded, so that the consequences of the former can indeed be far-reaching, to the extreme of Tertullian’s “Credo quia absurdum”.

Bearing these considerations in mind, we could reformulate the question in these terms: “When did the Myth of Western civilization originate: when was this myth born?” Nevertheless, changing the perspective only apparently clarifies the matter.

It would be like asking, “When was Europe born”? The answers we would get would differ significantly, depending on which roots and foundations Europe is supposed to rest. We could further change the point of view and deal with the question in these terms: “Which are the distinctive traits of the West and when and where did these first develop”?

“Olympias” – Reconstruction of an ancient Athenian trireme

Now, if we want to break the stalemate. the crux of the matter is to define what exactly Western Civilization is, because we cannot establish the date of birth or origin of something indefinite. Nevertheless, even in this case, we would be unable to provide a single answer, because even those who firmly believed that the West is an ascertained fact would give different and often contrasting and incompatible versions of it. Or, they would bundle together events and doctrines that do not fit well together, creating what I have called an artificial and motley construction, not unlike a Frankenstein or a Harlequin.

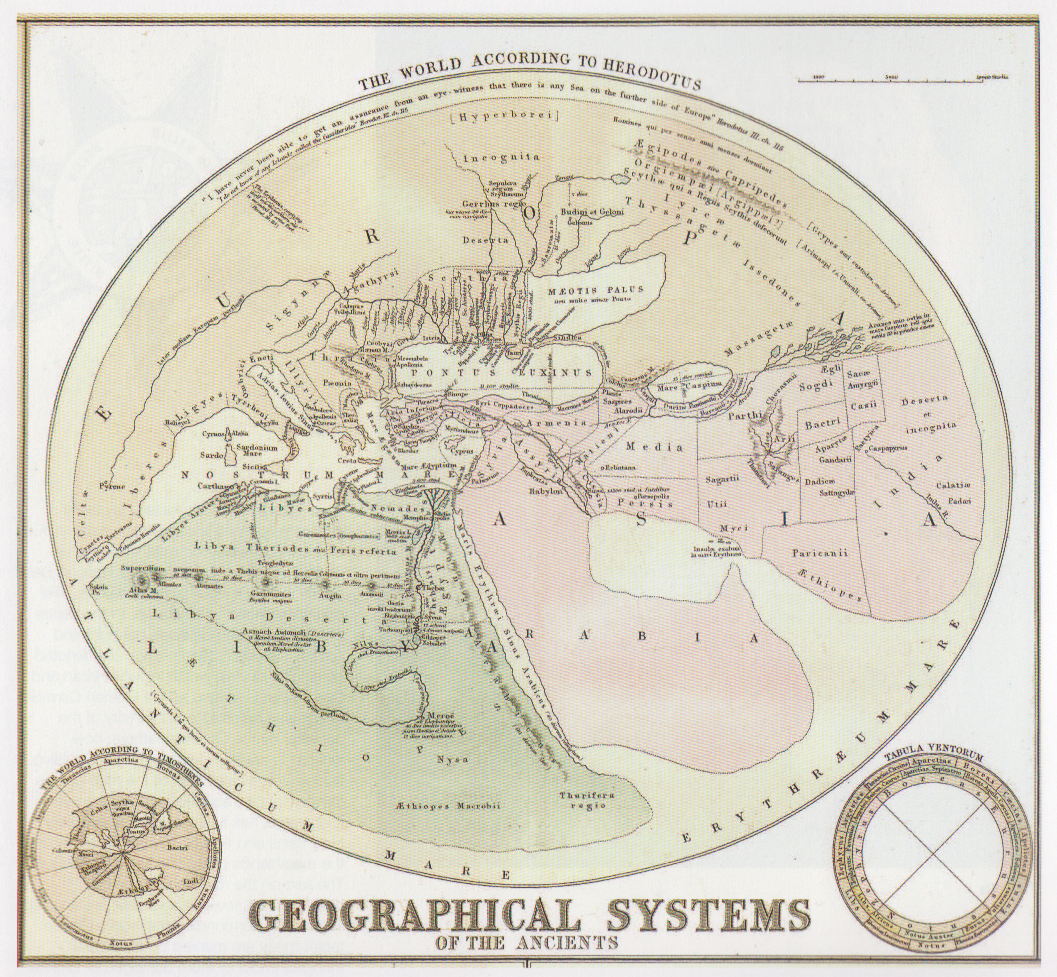

The identification between Europe and the West and, successively, between Euro-America and the West, is relatively new – it is an identification that occurs in the modern age. Nevertheless, it is a notion that goes back to antiquity, one that is based on the belief that there existed a historical, ancestral opposition between Europe and Asia. The West and Western Civilization would make sense only within an East-West dualism, as part of an opposition-alternative line of thinking stemming from the idea that Europe developed and defined itself in contrast with the eastern world – as an alternative to Asia.

This idea originated and developed in Greece in the decades following the second Persian War, the conflict that started at the battle of Thermopylae, continued at Salamis and ended at Plataea, with the final defeat of the Persians under Mardonius. The principal historian of the Persian Wars, Herodotus, was already claiming that the clash between Greece-Europe and Persia-Asia originated long before, at a time when the contours between legend and history were hazy. The conflict between Europe and Asia apparently started with the abduction of Helen, the last of a series of abductions carried out by both warring factions (Io, Europa, Medea), that triggered the reaction of the Greeks who had formed an alliance against Troy, the dominant power in the Near East. This legend – and a legend it is – was created and nourished by the Greeks themselves, who ignored information provided by the Greek sources, namely Homer and Herodotus. The Greeks ignored for example that the war between the Achaeans and the Trojans was in all effects a stasis, a civil war, a clash between peoples who spoke Greek and belonged to Greek culture, as I point out in my book, referring to arguments shared by many scholars. It should also be observed that even the Persian War was not only the clash between Achaemenid Persia and Greece but also a conflict among Greek cities and peoples, like Thebes and the Boeotians who fought alongside the Persians.

We can thus answer the initial question by affirming that the idea of the Europe-Asia divide, which lies at the root of the clash between the West and the East – the East of the Muslims, Turks and communists, etc. – originated with the Persian Wars, thanks to a legendary and ideological interpretation of the event by Greek historiography and culture.

Does the West have a history?

When speaking about the West, about the ‘Western civilization or model’, about ‘Western identity’, what is actually intended is the liberal-democratic system of life, which is characteristic of the USA and Europe – of ‘Western’ Europe, that is. We are, of course, talking about what was until not very long ago the ‘free world’ as opposed to the communism of Eastern Europe and Asia. Key features of the Western way of life are its freedoms, both political and economic. The Western way of life is governed by democratic regimes and its economy is based on ‘free initiative’ and on the ‘free market’.

When speaking about the West, about the ‘Western civilization or model’, about ‘Western identity’, what is actually intended is the liberal-democratic system of life, which is characteristic of the USA and Europe – of ‘Western’ Europe, that is. We are, of course, talking about what was until not very long ago the ‘free world’ as opposed to the communism of Eastern Europe and Asia. Key features of the Western way of life are its freedoms, both political and economic. The Western way of life is governed by democratic regimes and its economy is based on ‘free initiative’ and on the ‘free market’.

While these considerations are widely accepted, in Europe they actually make sense only if applied to the past 75 years of its history. The question appears in a totally different light if this dichotomy were to be intended as a reality consisting of elements that over the centuries have combined to forge an identity – elements that can somehow be connected to each other to form that historical continuity known as Western Civilization. Not unlike when we consider Christian Civilization, in all its diversity, as a system of life, a scale of values, in which the doctrine of Christ is both a point of reference and source of inspiration.

But which elements could be taken as being the distinctive traits that over the centuries have contributed to shape the West? Now, if we were to speak about Roman civilization, we could set its birth at 753 BC, its fall at 476 AD and mention a series of events where Rome played a central role: The history of Roman civilization is the history of Rome under the seven kings, of Republican Rome, of Imperial Rome established by Caesar Augustus.

Nothing of this kind can be said about the West and its presumed civilization. The West is not and does not have an identity that has developed over time; no date can be set for its establishment; it does not have a history to which the peoples of the West can relate. In over 2000 years, the so-called wester

n peoples – that is, the peoples of Euro-America – have fought each other: Europeans against Europeans, Americans against Americans, Europeans against Americans. The independence of the United States of America was the outcome of a revolutionary war against Britain, one of the great powers of Europe. A century later, the United States were torn apart in fratricidal war that lasted for three bloody years.

In other sections of this blog, as in many parts of my book, The Myth of the West, I have tried to show why any attempt in constructing a presumed European history is senseless. There is simply no point in establishing an affinity or a continuity between cultures and civilizations that are very distant from each other, as is the case with the Graeco-Roman world and Christianity or the latter with the notion of popular democracy. These realities did not develop in a harmonious and coherent succession, but through opposition and conflict. Christianity emerged against and as an alternative to Graeco-Roman civilization and democracy by imposing against the paramountcy of the people, political liberty and religious tolerance, the paramountcy of God and the Church, of a Revelation and monotheism, inflexible and exclusive, that rejected all other faiths, including those of Christian origin.

The history of the West is a history of ideological clashes and historical conflicts, and if we were to consider the west as synonymous with western people – that is, with the people living in Euro-America – we could affirm that their history is a recurrent stasis, the term used by the Greeks for Civil War.